08 Mar In the Middle of a Big Wide World

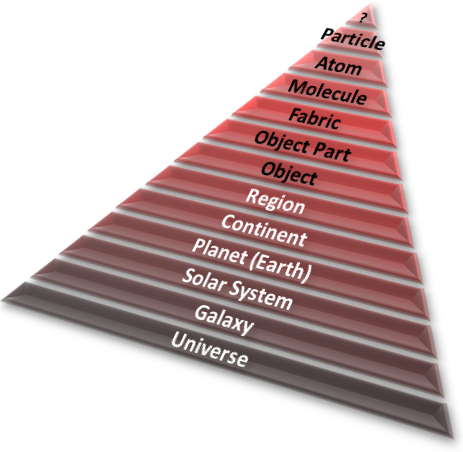

The guy on the previous post (Your Personal Bubble) represents your typical office worker who sees himself as part of a universal hierarchy or taxonomy, though not exactly where he’d rather be in the big wide world. Each moment, we each learn from our own vantage point. While we can learn about all physical things, from parts of atoms to the whole universe, most of us learn most about the middle-sized things. Our knowledge of the universe at the large end, and subatomic particles at the small end, is limited. We know they are there because we have developed ways of looking at them. We give things names and develop theories of relativity and quantum mechanics to describe our observations about them, but in the end, all we know about the universe and subatomic particles is that they are characterized by motion in patterns like waves or vibrations. Beyond the narrow confines of the middle, the rest is theory. This is the physical context of our existence. I define “context” as where we are physically in time and space, and otherwise (emotionally, socially, academically, spiritually, etc.), in the broadest possible sense.

The guy on the previous post (Your Personal Bubble) represents your typical office worker who sees himself as part of a universal hierarchy or taxonomy, though not exactly where he’d rather be in the big wide world. Each moment, we each learn from our own vantage point. While we can learn about all physical things, from parts of atoms to the whole universe, most of us learn most about the middle-sized things. Our knowledge of the universe at the large end, and subatomic particles at the small end, is limited. We know they are there because we have developed ways of looking at them. We give things names and develop theories of relativity and quantum mechanics to describe our observations about them, but in the end, all we know about the universe and subatomic particles is that they are characterized by motion in patterns like waves or vibrations. Beyond the narrow confines of the middle, the rest is theory. This is the physical context of our existence. I define “context” as where we are physically in time and space, and otherwise (emotionally, socially, academically, spiritually, etc.), in the broadest possible sense.

| Understanding Context Cross-Reference |

|---|

| Click on these Links to other posts and glossary/bibliography references |

|

|

|

| Prior Post | Next Post |

| Your Personal Bubble | The Context of Knowledge |

| Definitions | References |

| knowledge taxonomy | Taxonomy-Ontology |

| perception empiricism | Stanford on Ontology |

| fuzzy abstract | Calvin 1996 |

When we see things with our eyes, we can describe the knowledge we obtain as ‘empirical.’ When we use experimental techniques that rely heavily on visual observation and verbal or narrative description, we call those techniques ’empirical.’ When we learn things based on hypotheses, then use advanced equipment and rigorous experiments with controls to test the hypotheses, and rigorous proofs to exclude other interpretations of the results, these things are often categorized as scientific knowledge. Although mathematical and statistical techniques may involve some forms of observation and recording, they are often considered more reliable and less subjective than empirical techniques. Yet human perception, with its accompanying inconsistencies, is the most prolific scientific tool around, and it is the only equipment available in some cases. Many of the ideas presented in my posts, particularly in this section, are considered fuzzy because they are based on empirical techniques.

When we see things with our eyes, we can describe the knowledge we obtain as ‘empirical.’ When we use experimental techniques that rely heavily on visual observation and verbal or narrative description, we call those techniques ’empirical.’ When we learn things based on hypotheses, then use advanced equipment and rigorous experiments with controls to test the hypotheses, and rigorous proofs to exclude other interpretations of the results, these things are often categorized as scientific knowledge. Although mathematical and statistical techniques may involve some forms of observation and recording, they are often considered more reliable and less subjective than empirical techniques. Yet human perception, with its accompanying inconsistencies, is the most prolific scientific tool around, and it is the only equipment available in some cases. Many of the ideas presented in my posts, particularly in this section, are considered fuzzy because they are based on empirical techniques.

In the span of physical knowledge illustrated, we know the most about middle-sized things; mostly from “fabric” to “planet”. The other things we know about, to some extent, but every few years we throw out something really important we thought we knew, and replace it with something more plausible based on new evidence. What we may find at the ends, such as sub-subatomic particles (?) or other universes (not visible in illustration), remains to be seen.

Besides all things physical, there is another frame of knowledge, but it isn’t as nicely hierarchical as physical things because everything in it is abstract. Abstract knowledge includes concepts of time, action, reaction, value, likelihood, communication and understanding, and many other things that have no corporeal form. I choose a stack of precariously balanced spheres to visualize abstract knowledge. Lacking size and location, the interrelationships are muddled and difficult to pinpoint. This abstract frame of knowledge is equally important in our reasoning, which, by the way, we use physical mechanisms to learn, remember and consider.

Besides all things physical, there is another frame of knowledge, but it isn’t as nicely hierarchical as physical things because everything in it is abstract. Abstract knowledge includes concepts of time, action, reaction, value, likelihood, communication and understanding, and many other things that have no corporeal form. I choose a stack of precariously balanced spheres to visualize abstract knowledge. Lacking size and location, the interrelationships are muddled and difficult to pinpoint. This abstract frame of knowledge is equally important in our reasoning, which, by the way, we use physical mechanisms to learn, remember and consider.

I plan to lay out my ideas of physical and abstract knowledge as a foundation for a knowledge theory and ontology that will serve as a foundation for a computational theory for systems that can understand context, and thereby, understand people.

| Click below to look in each Understanding Context section |

|---|