03 Dec Language Expressiveness

Expressiveness

Human languages are eloquent vehicles for giving form to the motion of the human mind. They provide symbol-rich expressions for our thoughts and communications. Language is dynamic and defies circumscription. Yet, it is circumspect; it is also useful and extremely beautiful. To comprehend is to begin to capture that beauty.

The expressiveness of language is, in part, an element of its dynamic nature. Language is dynamic because words and expressions can be coined to accommodate new concepts or to express things in new ways. Far from a static entity, language is a metamorphic reservoir of intelligence, culture and art. To prescriptively criticize a fragment of language, spoken or written, with words like “this does not follow the rules so it is incorrect language” may be instructional, but it does not serve the speaker as well as the inherent flexibility possessed by language. Idioms are among the most used and important elements of language. Poetry, metaphor, lyrics and humor are some of the most beautiful and expressive forms of communication. How ironic that these are the things least likely to abide by the laws of grammar and diction.

The expressiveness of language is, in part, an element of its dynamic nature. Language is dynamic because words and expressions can be coined to accommodate new concepts or to express things in new ways. Far from a static entity, language is a metamorphic reservoir of intelligence, culture and art. To prescriptively criticize a fragment of language, spoken or written, with words like “this does not follow the rules so it is incorrect language” may be instructional, but it does not serve the speaker as well as the inherent flexibility possessed by language. Idioms are among the most used and important elements of language. Poetry, metaphor, lyrics and humor are some of the most beautiful and expressive forms of communication. How ironic that these are the things least likely to abide by the laws of grammar and diction.

Instead of simply opposing existing rules of grammar, our modeling approach attempts to reanalyze linguistic rule formulation and find a new way to capture the expressiveness of language. If the formalism is better able to capture the expressiveness of language, hopefully it will also be useful in cybernetic modeling of communicative behavior.

| Understanding Context Cross-Reference |

|---|

| Click on these Links to other posts and glossary/bibliography references |

|

|

|

| Prior Post | Next Post |

| Robot Neurons: Analog versus Digital | Probability of Understanding Meaning |

| Definitions | References |

| languages | Bailey 1996 |

| symbol | Moby Dick Quotes |

| metaphor | Scientific American |

Thoughts to Words

Just for a moment, take a step back from the discussion of language and consider a key component: words. What is the connection between words and the spreading patterns of activation in our brains, those hot-spots that develop as a result of excitation and inhibition? Science has not yet answered that question, at least not as of the writing of this sentence. Nonetheless, the transition from thoughts to words and back again is important to keep in mind as we try to develop effective automated language understanding systems.

Words need not be communicated to another. Consider that level of thought kept inside because we have no way of conveying the meaning. Bailey expresses it this way: “Our early, tacit, inchoate insights on a subject tend to remain ours alone, even though they might profitably mate with a colleague’s preverbal insights at a very low level” (Bailey, 1996). Before we can share our ideas, we must be able to put them into words.

Words need not be communicated to another. Consider that level of thought kept inside because we have no way of conveying the meaning. Bailey expresses it this way: “Our early, tacit, inchoate insights on a subject tend to remain ours alone, even though they might profitably mate with a colleague’s preverbal insights at a very low level” (Bailey, 1996). Before we can share our ideas, we must be able to put them into words.

Words are not the only focus of this discussion of language and communicative phenomena. Still, this transition from amorphous conceptualization of something, real or abstract, to nouns and verbs that express its essence must be replicated if an automated communication system is to work. Fractals may appear chaotic when viewed from a distance, but they exhibit recognizable patterns or mirrored structures when viewed up close. So, too, there is a distance we must travel from the chaotic structure of a thought to the regular structure of a word.

Communicative Phenomena

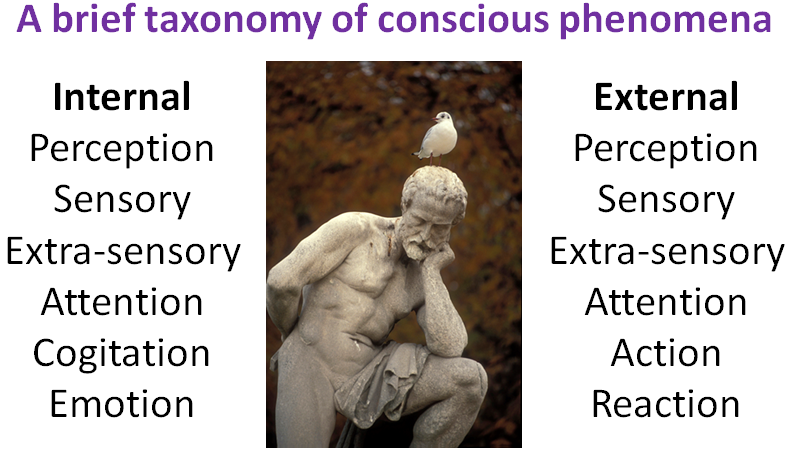

In other posts I have suggested that the conscious MIND exists distinctly from the brain – that the MIND includes the aggregate systems of the body. Conscious phenomena can affect decision making and motivate action, and can be articulated with language expressiveness. The illustration below shows a taxonomy of conscious phenomena, all of which are salient to our discussion of language (particularly attention, cogitation and action). The specific actions with which I am interested today encompass the phenomenon of communication.

Other than abstract types of communication such as telepathy and prayer, communication requires the physical body. We use our mouth and ears for verbal communication. We use our hands and eyes for sign language, reading, semaphores, and other forms of communication. Consequently, the actions of communication involve coordination with the same major brain centers as any other kind of action requiring a combination of thought and muscle coordination. The expressiveness of our symbolic language can change dramatically based on the physical articulation of our body language. In the next few posts, I intend to focus on the cognitive aspects of language, and how to model these in automata.

May I indulge and post some of my favorite poetry in all literature? Here is Ishmael – lone survivor of a truly harrowing adventure in the remarkable novel, Moby Dick, chapter 96. Poor Ishmael was lulled into sleep during a midnight watch when he had the tiller:

“Look not too long in the face of the fire, O man! Never dream with thy hand on the helm! Turn not thy back to the compass; accept the first hint of the hitching tiller; believe not the artificial fire, when its redness makes all things look ghastly. To-morrow, in the natural sun, the skies will be bright; those who glared like devils in the forking flames, the morn will show in far other, at least gentler, relief; the glorious, golden, glad sun, the only true lamp- all others but liars!”

| Click below to look in each Understanding Context section |

|---|