11 Jan The Pedantic Querulous Shrinking Violet

How much do you know about a person when you first meet them? What can you learn from speaking with them, even through an hour-long interview? Are first impressions valid in any way? Socially, we understand that it takes a variety of experiences in different contexts to really get to know a person, yet our ability to understand them depends heavily on our ability to adapt quickly – immediately – to what we perceive to be personality characteristics of the speaker that color their speech patterns and choice of words. The clothes they wear, their posture and carriage, tone of voice, facial expressions, humor, seriousness, direct eye contact, the speed of their gait, firmness of a handshake, movement when seated… a huge number of observable behaviors give us clues to the inner person, and we take them in and analyze them instantaneously.

How much do you know about a person when you first meet them? What can you learn from speaking with them, even through an hour-long interview? Are first impressions valid in any way? Socially, we understand that it takes a variety of experiences in different contexts to really get to know a person, yet our ability to understand them depends heavily on our ability to adapt quickly – immediately – to what we perceive to be personality characteristics of the speaker that color their speech patterns and choice of words. The clothes they wear, their posture and carriage, tone of voice, facial expressions, humor, seriousness, direct eye contact, the speed of their gait, firmness of a handshake, movement when seated… a huge number of observable behaviors give us clues to the inner person, and we take them in and analyze them instantaneously.

Whether consciously or below the surface, we often assign people to stereotypes or archetypes in order to better comprehend what they say. These stereotypes or archetypes form important pieces of our social framework. To me, the attributes pedantic, querulous and shrinking violet seem unlikely in the same person: the combination wouldn’t fit my framework.

| Understanding Context Cross-Reference |

|---|

| Click on these Links to other posts and glossary/bibliography references |

|

|

|

| Prior Post | Next Post |

| Shades of Meaning | Harmonic Convergence of Light |

| Definitions | References |

| context behavior | Karl Popper -BitBucket- -Koertge- |

| knowledge patterns | Skinner 1971 |

| conscious understanding | Dennett 1978 |

Instant Assessment

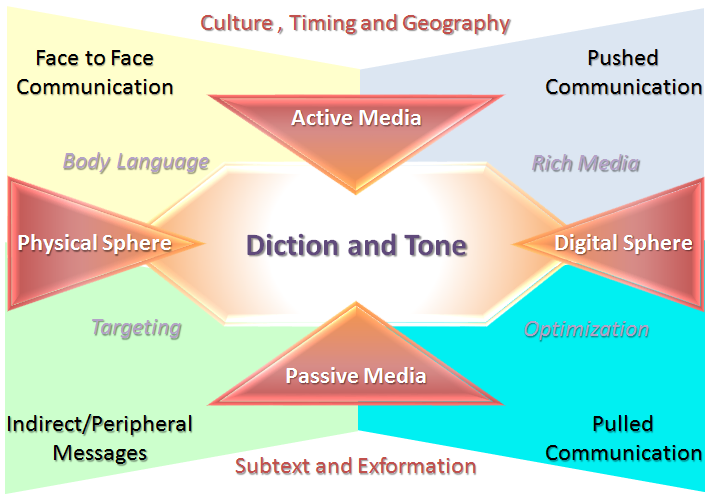

What in our brains makes it possible to correlate all these disparate inputs to create an instant composite of each complex social organism with whom we interact? When you meet a person, their posture, gaze and the shape of their lips tell much about how they enter the interaction. We describe walls that we  construct instantly to prevent or limit the emotional damage that may occur through damaged ego or emotions. We also like to preserve our perspectives and world view, thus we build fortifications around potential differences of opinion. If you were an animal lover and had never witnessed cock fighting or bear bating, how would you respond? Perhaps with horror. And then when you find a person you love likes to attend bullfights: what then? The amount of social acrobatics we perform in our minds to navigate the social distances between us and our friends is huge. Messages are laden with information from multiple sources as shown below.

construct instantly to prevent or limit the emotional damage that may occur through damaged ego or emotions. We also like to preserve our perspectives and world view, thus we build fortifications around potential differences of opinion. If you were an animal lover and had never witnessed cock fighting or bear bating, how would you respond? Perhaps with horror. And then when you find a person you love likes to attend bullfights: what then? The amount of social acrobatics we perform in our minds to navigate the social distances between us and our friends is huge. Messages are laden with information from multiple sources as shown below.

I have attempted, here, to illustrate not only the framework components of communication in the physical sphere of human interaction and communication, but components that are more applicable in the digital sphere of indirect “content” sent to us, or sought by us. I will address this framework more in future posts, but I want to get the overall interactions established as part of the dialog.

I have attempted, here, to illustrate not only the framework components of communication in the physical sphere of human interaction and communication, but components that are more applicable in the digital sphere of indirect “content” sent to us, or sought by us. I will address this framework more in future posts, but I want to get the overall interactions established as part of the dialog.

Inevitable Cognitive Dissonance

Naturally, the sub-conscious snap judgments we make prove somewhere between off-a-bit and completely erroneous. We discover this when the person says or does something that doesn’t fit the archetype we assigned to the person. To get beyond the inevitable cognitive dissonance created by snap judgments, we carry frameworks around.

Karl Popper quoted in Verbiage Overflow:

The myth of the framework can be stated in one sentence, as follows.

A rational and fruitful discussion is impossible unless the participants share a common framework of basic assumptions or, at least, unless they have agreed on such a framework for the purpose of discussion. …

In the formulation I gave of the myth, it is a fruitful discussion which is declared impossible. Against this I shall defend the directly opposite thesis: that a discussion between people who share many views is unlikely to be fruitful, even though it may be pleasant; while a discussion between vastly different frameworks can be extremely fruitful, even though it may sometimes be extremely difficult, and perhaps not quite so pleasant (though we may learn to enjoy it).

Do intelligent programs need to be able to handle cognitive dissonance or other inputs that create conflicting impressions? The closer we want to approach human competence, the more systems will need common frameworks and good exception handling and prioritizing algorithms, so they can deliver useful results even in the face of unusual or contradictory facts.

| Click below to look in each Understanding Context section |

|---|