07 Dec Curating Digital Meaning

Joe Roushar – December 2016

Joe Roushar – December 2016

That should be in a museum

I think of museums when I hear about curating. Meaning is, in a strange way, an artifact, simultaneously ancient and modern. Meaning has existed as long as perception has existed in the most rudimentary forms of life. For the purposes of my blog, I define meaning as: “the fruit of understanding and the fuel of action” (see my full definition in the glossary). By this definition, meaning may prompt a tiny organism with cilia to wiggle toward nutrients, or a budding entrepreneur to change the world with a new technology paradigm.

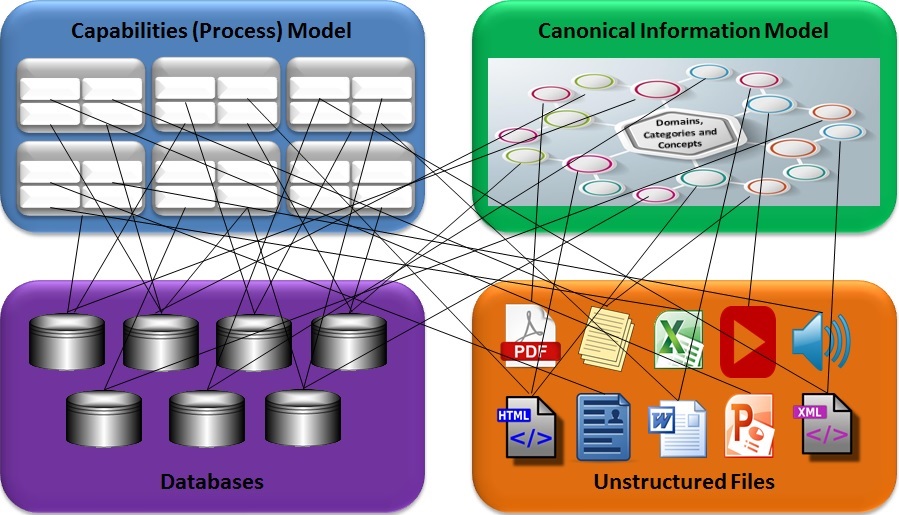

The new technology paradigm of this post is changing how people use enterprise systems: replacing queries and data requests, and keyword searches with meaningful dialog, and delivering actionable knowledge. This necessitates treating structured and unstructured digital content as knowledge artifacts, and changing the way we manage them. Managing meaning in communication is an art, and today I will try to reduce parts of it to a science.

| Understanding Context Cross-Reference |

|---|

| Click on these Links to other posts and glossary/bibliography references |

|

|

|

| Prior Post | Next Post |

| Architecting Meaningful Relationships | 2017 – The Year of AI |

| Definitions | References |

| meaning searching transformation | capabilities SnapLogic 2008 |

| convergence understanding | McCreary 2014 |

| database tags deep web | Roger Costello 2008 |

Digitally Understanding Meaning

In our world of specialization, the people who are very good at understanding and managing content, are often less good at defining and implementing processes, and the process folks often don’t have as much appreciation for content. But businesses need to be good at both process and content to be more competitive in today’s information economy. According to the analogy of the lost timepiece in the desert, meaning doesn’t exist outside the brain, and as soon as the brain is no longer able to process it, there is no more meaning. The things I have been describing in Understanding Context will not change the things businesses need to do to compete. Sales, marketing, IT, operations, R&D and everything else will still need the same capabilities. This paradigm shift creates a new, largely automated set of processes around repackaging information assets as knowledge assets. One key process in this transformation, is that of curating meaning in and for automated systems.

The title of this blog implies that context is somehow important and understandable. To be understandable, the context must first be meaningful. Meaningfulness is a prerequisite to understanding chaotic mountains of digital content. Chaos is not internally understandable until it is calmed and sorted out, though its components may be separately understood. The Japanese verb for “understand” is wakaru (分かる). It is built on the same root as wakeru (分ける) which means “to divide into, or separate”. Cognitively, you might say wakeru is to actively classify concepts and wakaru is to derive meaning from the classified concepts. I propose that the most important process in creating and curating meaning is classification, whether performed by humans, machines or both.

From the Beginning

Converting computing systems from information to knowledge processors has been a longstanding challenge. Some have approached it from the top-down using enterprise canonical models or ontologies as concept graphs to depict the big picture of meaning in the business. Some have started from the bottom-up mapping individual systems and the conceptual interactions within the system, and sometimes with the content in other systems. Both are necessary, but not sufficient without an elegant model to connect the separate subsets of meaning to the broader enterprise model. I think encoding the needed knowledge cannot be done in a way that scales to enterprise volume without strategies to reduce the amount of effort humans need to manage and interpret meaning from the top and from the bottom. Reducing this volume of work can be done by delegating cognitive tasks, such as mining and discovery, to automated bots, and formally creating, encoding and curating meaning metadata through supervised learning. Meaning metadata may include:

- Topic metadata – the conceptual topic(s) contained in the information

- Canonical Context metadata – how the information is related to other information in the organization

- Authorship metadata – the people involved in the content creation

- Sensitivity metadata – the level of sensitivity or groups that are permtted to access

Creating content is sometimes described as “authoring”, though for video and audio content, “recording” is a common verb. When the content is data in a structured database, the creation process may be called “transacting”, “ordering”, “data entry” or any number of other verbs descriptive of either the process or the output. Creating is often considered the first major step in of a process, but, as a brain task, creation either includes or is preceded by conceiving: the idea precedes the artifact.

Creating content is sometimes described as “authoring”, though for video and audio content, “recording” is a common verb. When the content is data in a structured database, the creation process may be called “transacting”, “ordering”, “data entry” or any number of other verbs descriptive of either the process or the output. Creating is often considered the first major step in of a process, but, as a brain task, creation either includes or is preceded by conceiving: the idea precedes the artifact.

The quality or completeness of the content may be improved by further “editing”, “redlining”, “data enrichment”, “data validation” or “data cleansing”. As I am authoring this page, I am attempting to enrich it with images, such as that of an iconic author whose authoring process is celebrated. This may or may not actually improve readers’ understanding or enjoyment of the content, but we speak of content other than text as “rich media”. Data enrichment usually means adding desired information that was not in the original data. The processes that bring content through its lifespan may occur in sequence, and even in cycles. The activities of “tagging” and “curation” are often applied to processes that describe the content in ways that are both meaningful and digitally consumable.

Meaningful Metadata

When you read a typical web page (HTML), there may be lots information embedded in the text that you don’t see because the display shows or “renders” some of the information and hides some it. The hidden information includes instructions to the software that renders the page about where paragraphs begin and end <p>, which text should be larger, smaller, boldfaced <b>, italicized or shown in different colors. These instructions are called tags, and many tags are used for other purposes, including providing metadata about the page for search engine optimization (SEO). Managing SEO tags is a classic example of what is meant by “curating”.

Tagging content with information about the content can be done for content other than web pages. Images and videos may have embedded tags in the file header, for example. But tags do not need to be embedded to provide value, as long as there is a reliable way to associate externally stored tag metadata with the correct information assets. A metadata repository may be designed and implemented as a file or database in which each metadata entry contains the tags and the reference to the information asset they describe. It is interesting that the current preferred version of HTML5, many tags that used to be embedded in each page are, instead, stored separately in a “Style Sheet”.

Consumable Metadata

Consumable Metadata

As with all words, consumability is very ambiguous. IBM has used the term to mean “a client’s complete experience with a technology solution beginning with buying the right product to updating it.” This is not what I’m talking about. Digital consumability, in the context of this discussion, is about getting metadata into more accessible formats, so that, in addition to human readers, systems and processes (such as heuristics) that may benefit from the metadata, can get it and use it. Many Legacy computing systems are not good at adapting their behavior based on external data or metadata. But as more “services”, micro-services, and cognitive computing systems arise in an IT ecosystem where APIs facilitate interconnections between systems, the importance of rich consumable metadata increases, and creates opportunities to add intelligence to existing processes using services.

The processes we define to manage and consume metadata in the coming years will help move the world from the information age to the age of knowledge.

Remember the discussion on generalization in learning, and the one on generalization procedures in inference? When we divide the world, and the sensory stream of conscious perceptions into neat buckets of color, shape, sound in our minds we are constantly classifying in ways that effectively generalize and dissect concepts. The buckets into which these concepts find their way are associated with one another by causal and taxonomical connections, and may be further associated with specific places and times. This leads us to four types of attributes we may include in our metadata:

- Causal metadata – processes that make data what it is

- Taxonomical metadata – how data fits into the grand scheme of all information

- Place metadata – when applicable the geographic limits of the data’s reach

- Time metadata – when the data came to be and when it is “effective”

All these buckets and connections can be depicted as graphs of meaning, and the clustering of related concepts form contexts that further contribute to understanding. I believe human understanding processes use a general taxonomy of meaning to classify concepts into the universe of possible contexts and implications, and specific experience-based graphs to derive understanding.

Likewise, enterprise information can be made much more understandable, even actionable, when enough accurate and complete metadata is associated with information assets.

There is a huge gap in automated tools needed to get and use multi-source omni-structure information: we don’t have many good tools to automatically scan content to infer the meaning of digital assets and assign them homes in the enterprise semantic model. There are some rudimentary examples of tools designed to create, capture, manage and deploy meaningful content, and how the experiences can apply to semantically managed enterprise capabilities. I will discuss some of these in my next post. The takeaway for today is that architecting the processes used to manage the content, and its metadata, is critical to the success of efforts to make the bits and bytes of all the assets in the enterprise meaningful enough to enable cognitive computing systems to deliver actionable knowledge.

| Click below to look in each Understanding Context section |

|---|